Background information

Can you prove a photo is real?

by David Lee

There should be transparency around whether an image, article or video has been created using artificial intelligence (AI). The thing is, transparency’s not all that easy to achieve. While Instagram is the most recent example of this, it’s just one of a series of spectacular failures.

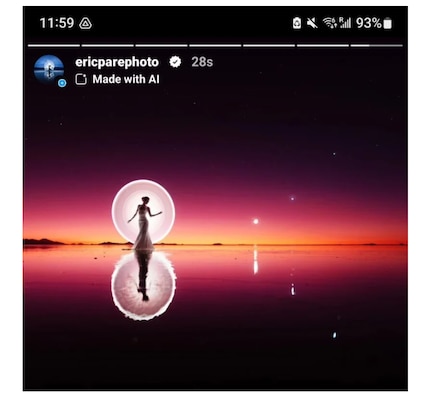

Transparency is important when it comes to AI-generated content. Meta, the corporation behind Facebook and Instagram, wants to label AI-generated images in order to prevent users from being misled. In May 2024, it began marking some Instagram images with a «Made with AI» label. At least in the United States. Personally, I’m yet to see the label in use. It doesn’t seem to have been activated in Europe yet.

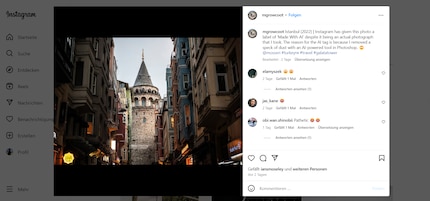

While the company’s efforts are commendable, there’s just one tiny problem – it doesn’t work. There have been numerous reports of Instagram labelling genuine photos that definitely weren’t generated with an AI tool, angering the photographers who took them.

It’s still not entirely clear why this is happening. Meta hasn’t divulged much information on how exactly these labels come about. What we do know is that the company relies on watermarks written into the metadata by the AI tools themselves. However, this can be easily sidestepped, for example, by uploading a screenshot of the image instead.

Plus, Photoshop uses AI technology, for example when retouching or removing noise. Adobe is part of C2PA, an organisation dedicated to transparency around creative content. I suspect Photoshop indicates when a photo has been edited using AI in the metadata for transparency reasons.

But using AI-powered techniques doesn’t mean a conventionally shot photo is «made with AI». Far from it. Airbrushing a bothersome blemish out of a photo is totally different to generating an image from scratch using Midjourney, Dall-E or Stable Diffusion.

Content credentials, a type of encrypted digital watermark, are used to prove the authenticity of photos and make each step in the editing process transparent. This includes AI-powered edits. The goal? To fully document the creative process.

This kind of encrypted metadata allows creative professionals to prove they’ve done what they’ve done. However, it doesn’t work the other way around. You can’t use watermarks to prove that a photo _ isn’t_ real.

The whole idea is based on the fact that creators themselves are interested in transparency. It’s not suited to exposing trickery. But that’s exactly what Meta wants to do.

So if using watermarks to detect AI doesn’t work, what will? One common method is using AI-powered AI detectors, but this has never worked.

Professors are keen to use AI to check whether their students’ papers were written using an AI such as ChatGPT. OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, was working on a detector for this, but pulled the plug in 2022. The justification for the move was intriguing: no AI detector has ever been even halfway reliable. And apparently Open AI saw no sign of that changing in the foreseeable future.

These detectors use the same methods as generative AI. Both are based on machine learning – pattern recognition based on large volumes of text as training material. Detectors examine the extent to which a text deviates from the style of a known AI such as ChatGPT. This, however, is how a circular problem arises. ChatGPT and the like imitate a human’s writing style and are trained on the basis of text written by humans.

There may be such a thing as a typical ChatGPT style, but that’s just the default setting. A setting that can also be changed. These generators – be they for text, images, or music – are still very flexible in style. They can imitate genres or even individuals.

The details of this might be different for images than for texts. However, the fundamental problem remains. An AI designed to reliably detect AI would have to be much more advanced than – or at least work in a completely different way to – the AI tool it’s checking. But there’s the rub. Pattern detection and pattern generation are rooted in the same technology.

As long as nothing fundamental about that changes, we’ll continue to see this annoying mislabelling issue.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all